March is Women’s History Month here in the United States, which means we’ll be shining the spotlight and celebrating some of the most powerful and influential women in history all throughout the month. You’ve likely heard of some of them, learned about others in school, and will hopefully get to know others who may not have enjoyed as much prominence in the history books. Nevertheless, every one of them made their mark on the history of the world and during their lifetime!

This week, we’re focusing on four important rulers. We’ll begin with a pharaoh; no, not Nefertiti or Cleopatra, but one of the first women to rule as pharaoh of Egypt.

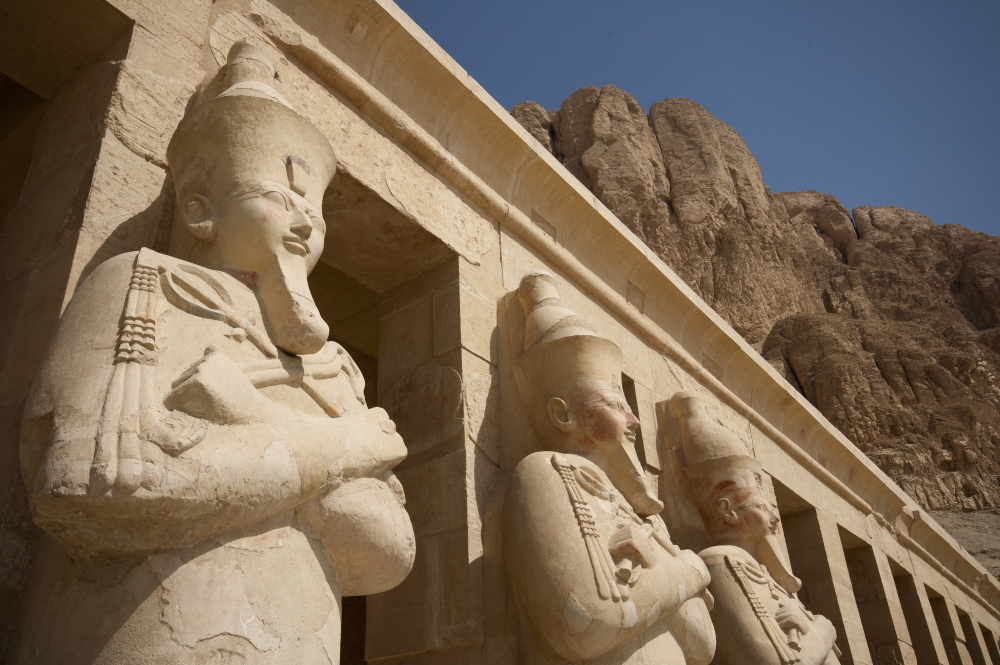

Hatshepsut – Pharaoh of Egypt

c. 1508 – 1458 BCE

Portrait of Queen Hatshepsut — Temple of Hatshepsut, Luxor, Egypt

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I. She became queen of Egypt at around age twelve when she married her half-brother Thuthmose II—the son of her father’s second wife.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: Remember that for several millennia, rulers often looked to keep bloodlines close; as such, this union between siblings wasn’t considered unusual.

There’s a consensus amongst historians that Thutmose II was a rather frail and uninfluential ruler—a stark contrast to his sharp wife, whom statues depict standing dutifully at his side. Together, they had a daughter, Neferure, but no son. As a result, when Thutmose II died at a young age, the path to succession would result in the throne passing to a son bore by another wife.

The child who would become pharaoh was accepted as king even though he was too young to rule, himself. As was custom, his stepmother, Hatshepsut, became regent: a temporary ruler over the country until the child came of age. However, within a few years of her husband’s death, she would ascend as pharaoh, herself.

There’s some debate as to how many female pharaohs had ruled in the 1,500 years before Hatshepsut; consensus says two, maybe three. Cleopatra—perhaps the most well-known female pharaoh—wouldn’t take the throne for another 14 centuries.

Hatshepsut’s 21 year reign was one of peace and prosperity for Egypt. The period produced beautiful art, along with impressive architectural and cultural accomplishments. She was one of her civilization’s most prolific builders, and produced so much art that nearly every modern museum with a collection from ancient Egypt contains relics from her rule. She also re-established trade routes that had been previously disrupted by occupation: amassing wealth and establishing a thriving economy during her dynasty.

Her mortuary temple was a prime example of the majesty of her reign: a towering monument which included murals of trade expeditions to the ancient kingdom known as the Land of Punt.

There’s debate amongst historians as to why Hatshepsut is depicted with male clothing and a beard in much of the imagery from her time. Was it pure ambition to achieve the god-like status that the male pharaohs of ancient Egypt had held? Was it justification to ancient Egyptians who were long accustomed to pharaohs being male? She was, after all, the stepmother of the king—young as he was. No female ruler before her had a male co-ruler for whom to account.

As with many stories from the ancient world, historians must piece together the tale of Hatshepsut’s life and legacy from pieces collected from a variety of sources. Thus, we will never know everything about her, leaving us with some mystery.

When she died in 1458 BC, her stepson—believed to be in his early 20’s at the time—finally ascended to the throne of Egypt. Historians tell of his loathing for his stepmother and predecessor; during his rule, monuments to Hatshepsut, statues of her likeness, and records of her rule were destroyed. When the remains of these stone pieces were discovered, the pieces ranged from the size of a grape to boulders that weighed over a ton. Her mummy was even removed from her original grave; one believed to be Hatsehpsut was eventually unearthed in the Valley of Kings in 2007.

Historians speculate this erasure campaign was fueled by a desire to delegitimize Hatshepsut’s position as pharaoh—though as we know today, this effort failed, and Hatshepsut is now known to have been one of the greatest pharaohs in ancient Egypt .

This tale ends with her own words from an inscription on one of her obelisks at Karnak:

“Now my heart turns this way and that, as I think what the people will say – those who shall see my monuments in years to come, and who shall speak of what I have done.”

Wu Zetian – Empress of China

624 – 705 CE

Wu Zetian (625-705), Empress of China, 7th-8th century

Wu Zetian is the only woman in over three thousand years of Chinese history to rule in her own right.

Wu entered the palace of Tang emperor, Taizong, as a junior concubine at the age of 14. Accounts from the time depict her as very beautiful, unusually well-educated for a woman of her time, and strong-willed. After the death of Taizong, she was sent to live the rest of her live in a convent—as was custom for the concubines of an emperor after his passing. However, the new emperor, Gaozong, brought her back to court, where she became his favorite concubine and bore him four sons and one daughter.

Her husband, Gaozong, was too ill to attend to matters of state, and notably weak in character. He relied heavily on Wu, which allowed her to grow her power and influence unlike any empress before (or which would follow) her. In the later years of his life, Gaozong relied on her entirely: positioning her to effectively rule China on her own.

Wu was undeniably ruthless: identifying those who sought to take her throne and eliminating them—a tactic even employed against her relatives. After Gaozong’s death, he was succeeded by his and Wu’s son, Li Xian—known as the Zhongzong Emperor. Zhongzong had, himself, married a concubine who tried to assert herself into a position of power and influence like that of her mother-in-law. After one month, Wu deposed and exiled Zhongzong and his wife, replacing him with another son.

Whilst her second son sat on the throne, Tang loyalists revolted. This rebellion was crushed within weeks with the cooperation of armies loyal to the throne. Wu had undeniable support from public servants—further evidence of the strength and reach of her power.

Wu would govern the empire with great efficiency. She selected capable and loyal men to serve in her government and paid no heed to social standing in their selection. She was an excellent administrator, decisive and ruthless to opponents, and was unafraid to act with courage—all of which won her the respect of her court.

Throughout her rule, she drove substantial shifts within Chinese society. Where it had previously been dominated by military and political aristocracy, it became one governed by scholarly bureaucracy drawn from the gentry. Her reign was prosperous and peaceful; she prevented wars and welcomed ambassadors from as far away as the Byzantine Empire. She heeded her loyal ministers and often acted on their criticisms. She was also the era’s most important early supporter of Buddhism: a faith that would surpass the influence of the Confucian and Daoist faiths throughout China.

Wu also inspired societal changes to benefit other women in Chinese society. One such change was to the customary mourning tradition—previously restricted to the fathers of a family—to include the children when mourning the loss of a mother.

During her reign, military expenses were reduced, taxes cut, salaries of deserving officials raised, retirees were given a viable pension, and vast royal lands near the capital were converted to farmland. After reigning for more than 14 years, she was forced to hand over the throne to her eldest son. Ten months later, she died at the age of 81.

Her legacy is controversial, with historians often focusing on her ruthlessness and methods for keeping power: qualities that were notably mirrored by countless male equivalents throughout history. Her giant stone memorial—placed at one side of the spirit road leading to her tomb—remains blank: the only uncarved memorial tablet in more than 2000 years of imperial history.

Isabella I – Queen of Spain

1451 – 1504 CE

An engraving of Isabella I of Castile, Queen of Spain

Isabella was born second in line to the throne of Castile. Her path to rule was muddied by several uncertainties in her life: her father’s death; a turbulent rule by her older half-brother, Henry IV; a rebellion by nobles; and the death of her younger brother Alfonso.

Henry agreed to name her heir-presumptive, and that he would not force her to marry against her will. After several failed attempts to marry her to politically beneficial suitors, she wed Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469 after they eloped to be together. Their union brought together the Castile and Aragon regions, and their rule would also bring about the permanent union of Spain and the beginning of an empire.

Isabella was left with many challenges after the problematic rule of her half-brother, Henry: rampant crime and debt being two of the largest. To address the first, she established a police force known as “La Santa Hermandad” (the Holy Brotherhood) to work under the crown. Previously, groups of crime fighting individuals would band together and vaguely report to the nobility.

To address the issue of debt, Isabella corrected pricing on lands sold by Henry while offering exemption to churches, hospitals, and the poor. She also brought currency under control by reducing the number of establishments authorized to mint coinage.

Isabella and Ferdinand worked to improve the government structures and processes put in place by their respective predecessors. Isabella felt the need to have a relationship with her people, so she and her husband set aside time every Friday for their subjects to bring their troubles and complaints to them.

Isabella’s reign also saw the rise of exploration as European powers sought to expand their influence and trade during these years. In an effort to establish the Spanish Empire as a key empire in Europe, Isabella funded Christopher Columbus—after arresting him and other explorers for capturing native men to be enslaved—to lead Spanish expeditions across the globe. In her will, she mandated that her descendants not allow the indigenous peoples of the Americas to lose their freedom and property, and to right any wrongs committed against them.

Her 30 year rule saw great change in her beloved kingdom. She and Ferdinand grew their family and, through their children, built ties with other European royal lines. After the loss of two of her children, Isabella began to decline, eventually passing away in 1504 (aged 53). In 1974, she was given the title “Servant of God” by the Pope to celebrate her legacy in Spain and around the world.

Elizabeth I – Queen of England

1533 – 1603 CE

A portrait Queen Elizabeth I, ruler of England from 1558 – 1603

Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn. Henry—probably best known in contemporary history for his six wives—had Elizabeth’s mother beheaded for accusations of treason and adultery when Elizabeth was only two.

Elizabeth was given a royal upbringing, though she didn’t live with her father. She was well educated, fluent in five languages, and taught a variety of academic subjects. She inherited intelligence, determination, and shrewdness from both her parents.

She was also third in line to the throne behind her brother, Edward, and sister, Mary. Edward became King but only reigned for 6 years—ruling from the age of 9 to 15. After his death from illness, his Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey, ruled for only nine days before being deposed by his half-sister, Mary. Mary’s tumultuous reign saw her trying to return England to Catholicism and briefly incarcerating Elizabeth in the Tower of London for implication in the Wyatt Rebellion.

After Mary’s death from illness in 1558, Elizabeth became queen at age 25, and would continue her rule for the next 45 years. Under Queen Elizabeth, exploration and trade expansion would flourish, as would the arts; the era would produce artists (such as Hilliard and Gheeraerts) and composers (including Byrd and Tallis) that are still well-known today.

However, it wasn’t only smooth sailing for Elizabeth. She had to deal with threats of invasion from Spain and France, rebellion in the north of England, and the influence of European and religious politics on her kingdom.

Elizabeth was given the moniker “The Virgin Queen” and is famed for never marrying. In her time—and especially as a royal—this was most unusual. A carefully planned marriage could bring a host of political benefits, cement relationships with other nations, and provide an heir to continue the Tudor lineage. Whilst she entertained marriage prospects, she used them to her advantage and never followed through with a commitment to marry.

Rather, she spoke of being married to the country of England, and her life as a single woman was seen as an act of selflessness: sacrificing potential personal happiness to stay focused on the good of the nation. It cannot be denied that by all accounts she was very popular with the majority of her subjects, earning the affectionate nicknames “Good Queen Bess” and “Gloriana”.

Her shrewd and decisive leadership brought great successes to England during periods where great dangers existed at home and abroad. She did not wield absolute power, but nevertheless upheld her authority in order to make critical decisions and set central policies for both the church and state.

Upon her death in 1603, the Stuart era of English history began with no heir to the Tudor line; yet, to many, “Elizabethan England” is viewed as a prosperous, cultured, and thriving era for the nation. Though she left no child, no spouse, and no heir, her legacy lives on.

Selecting just a small number of women to feature this month has been a difficult task. We encourage you to discuss and share the female figures from history that impress or inspire you!

If you’d like to learn more about some amazing women of history, we recommend the following resources:

- Women You Should Know (website)

- Rebel Girls (podcast)

- Rejected princesses (Instagram account)