—Guest blog written by Kat Fritz (2021) and edited by Grace Rojas (2022)

February 1st marks the beginning of Black History Month in the United States. In honor of this month, we will be sharing stories of Black individuals who contributed to the formation of the United States. You may be familiar with some of the figures we have highlighted or maybe this is your first time learning about them and their contributions; either way, our team would like to encourage you to read and share their stories. In addition, to aid your educational journey on Black History Month you can visit blackhistorymonth.gov .

♦ ♦ ♦

Peter Salem (c. 1750 – August 16, 1816)

Peter Salem was born into the institution of slavery in Framingham, Massachusetts; though the exact date of his birth is unknown, his hometown celebrates it on October 1. His original enslaver was Jeremiah Belknap, who later sold Salem to Major Lawson Buckminster.

In early 1775, Buckminster offered a proposition to Salem: if he joined the militia, Salem would be granted his freedom. Since well before the Revolutionary War, Black Americans had been barred from serving in militias, so many enslaved men saw the offer of military service as a new opportunity to secure their freedom. However, the British also offered freedom to any Black Americans who joined their forces. Between 5,000 and 8,000 Black Americans would ultimately serve in the American Continental Army, and at least 20,000 in the British forces. Several thousands of Black soldiers from both sides secured their freedom as result of their service in the Revolutionary War, including an unprecedented number who were manumitted—freed from slavery by their enslavers.

Thus, Salem enlisted as a minuteman in Captain Simon Edgell’s Framingham company on the side of the American colonies. By April, Salem was serving in the Massachusetts militia as a minuteman under Captain Thomas Drury’s company in Colonel John Nixon’s Fifth Massachusetts Regiment. The soldiers were mostly white, but Salem also served alongside other Black minutemen: including Seymour Burr, Titus Coburn, and Salem Poor. After fighting in the bloody Battle of Lexington and Concord, Salem found himself on the front lines during the Battle at Bunker Hill. On June 17, 1775, Major Pitcairn of the British Royal Marines—the highest-ranking officer left on the battlefield—gathered his troops for a motivational speech before the attempt to capture Bunker Hill.

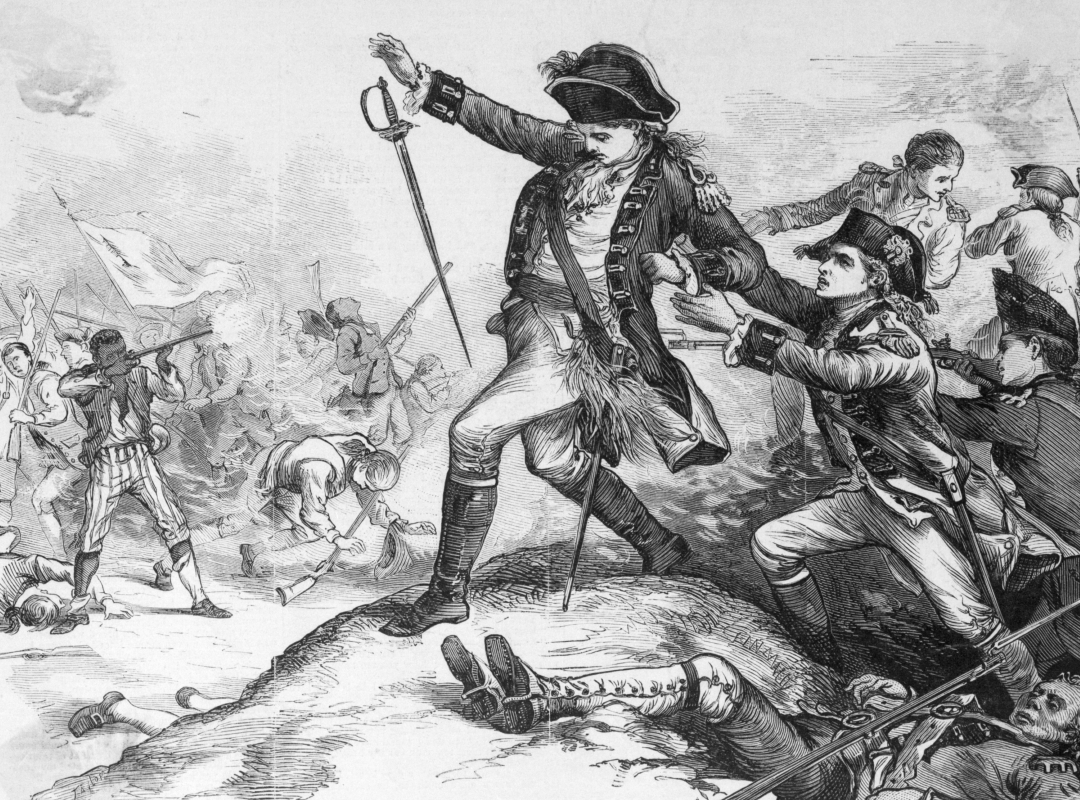

As Pitcairn led the final charge over the Continental redoubt, Peter Salem reportedly raised his rifle, lined up his sights, and pulled the trigger; the bullet struck true, fatally wounding the Major. While the Continental Army lost the battle, killing a significant British officer boosted the morale of the troops and allowed them to retreat safely. Additionally, the British suffered many casualties. Salem emerged as a hero, and the Major’s death bolstered the Continental troops to rearm and continue fighting.

An engraving depicting the shooting of Major Pitcairn by the African-American soldier, Peter Salem, at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Soon after the battle, the Massachusetts General Court gave Salem a commendation for his bravery and valor at Bunker Hill. His fellow soldiers allegedly collected money to present Salem to General George Washington as the man who shot Major Pitcairn. Salem continued his service in the Continental Army until he was discharged in 1779. In 1783, he married Katy Benson, built a small house in Leicester, Massachusetts, and took up work as a cane weaver.

Along with providing men like Peter Salem a chance to secure their freedom through military service, the American Revolution also provided freedom-seekers an opportunity to flee from slaveholders. During the British invasion of Virginia, some 5,000 enslaved people in Georgia and 20,000 in South Carolina—a quarter of the estimated enslaved population—escaped to freedom. However, the war also had inconsistent effects on the institution of slavery; though the Revolution inspired and fortified Black resistance to slavery, the northern and southern divide increased. Northern states gradually adopted emancipation structures—some abolishing the institution of slavery altogether. Conversely, White southerners relied on exploiting the Black population for economic gain, so the South resolved to strengthen the institution.

Free Black Americans were inspired by the natural rights philosophy of the time, which was outlined in the Declaration of Independence:

Because of contributions to the war from Black soldiers like Peter Salem, Black Americans had proof that American ideals contradicted the existence of slavery. Peter Salem had performed his duty as an American soldier just as well as White soldiers. Over time, freed Black Americans argued against the slave trade and the institution of slavery; this was the beginnings of the abolitionist movement.

Despite Peter Salem’s significance in the Revolutionary War, he died at a poorhouse in his hometown of Framingham, Massachusetts on August 16, 1816. Salem was buried in a pauper’s grave; though in 1882, the citizens of Framingham erected a gravestone monument at his burial site.

Salem’s role in the Battle of Bunker Hill symbolizes the determination of all Black Americans during the eighteenth century. White patriots fought for their right to live freely and without the oppressive British rule. Similarly, Salem fought to secure his own freedom from the racial inequality ingrained in the history of the United States. Though little is known about Peter Salem, his existence as a Black military hero was significant during a time when the United States permitted few if any freedoms to Black Americans.

♦ ♦ ♦

We encourage you to read, learn and visit blackhistorymonth.gov for more information about African American heroes and leaders in American history.